Shanghai Food & Drink Buzz: February 2026

Your trusted source for Shanghai’s F&B happenings

April 23, 2023

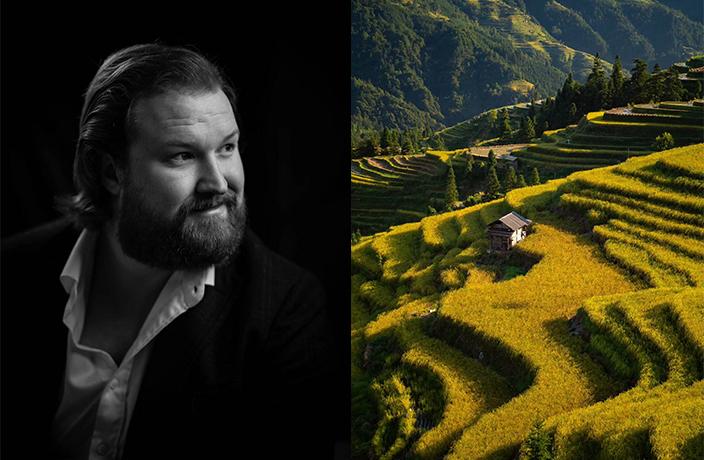

Born with an insatiable hunger to look deeper, understand more, and explore the stories behind mundane aspects of life most of us take for granted, Graeme Kennedy chose to pick up a camera.

He has photographed everything from mushroom harvesting in Lishui to surfing culture in Hainan, from agave farms in Mexico to cacao production in Tanzania.

Averaging hundreds of thousands of photos annually, Graeme’s motto is: “Just say yes.” And that motto has opened doors for him in some of the remotest corners of the globe.

This is his story.

Where are you from and what brought you to China?

I was incredibly fortunate to be born in a beautiful town in the Canadian Rockies called Jasper – a small town of 4,000 people at the heart of an incredible, sprawling mountainous National Park.

I grew up surrounded by fresh air; the forests were alive with birds, bears and elk.

My weekends were spent climbing trees, skiing, biking and pulling pranks on tourists who had travelled from all over the world to see this gorgeous place I called home.

Sadly, all of that was lost on me. Growing up, all I wanted was to leave that town, and even before I finished high school, I had left home to move to the nearest city, Edmonton.

I dug deeper into the arts, dabbled in radio and music production, stage lighting and sound – really anything I could get my hands on.

It wasn’t enough. My itch to see more led me to the marketing department of a school in Thailand, then London, and then eventually the opening of an international school here in Shanghai.

I knew nothing about China. The Canadian education system taught us the state capitals for all the American states, but virtually nothing about one of the most ancient, diverse and fascinating countries in the world, China.

I knew it was a big country, and I knew there was a large (and great) wall somewhere, but my impression was grey, uninteresting and mostly informed by political stories I saw on the news.

I figured that couldn’t be the whole story, so I bought a one-way plane ticket.

How did you get into photography?

Photography for me has always been a key. It opens up doors, gives me an excuse to travel with more purpose, and lets me see behind the scenes.

It also helps to slip out of awkward small talk at parties – “Better get back to taking photos, nice to chat!”

It didn’t take long for me to realize that what I really wanted was to simply see more, understand more, hear more stories, meet more interesting people and go through more ‘staff only’ doors to see how businesses really work.

The access you get with a camera is incredible – from spending time with the late Queen of England, to sitting in a dugout canoe with a bunch of researchers in Sierra Leone watching a family of hippos bob up and down as the beginning of an Ebola epidemic flared up around us. True stories.

How did you make photography your full-time profession?

I spent my first few years in Shanghai working in Marketing and Creative Direction for Wellington College and naked Group.

It wasn’t long before I realized that this country is too big and interesting to spend my days sitting behind a desk, so I knew something needed to change.

I went to Peru for a summer to capture stories along the chocolate supply chain with my friend Julia Zotter, one of the owners of Zotter Chocolates, an Austrian chocolate manufacturer.

It was clear to me during that trip that I wanted to be a photographer full time, to dive deeper into how things work. It’s incredibly easy to kick the can full of your dreams down the road, and I had been doing that for too long.

Starting your own company is always a little bit of a leap of faith, and so many people I know are waiting for the right moment. I was too, but I understand now there really never is the right moment; you just have to go for it.

Even so, up until the very last minute I was still searching for solutions other than starting my own company – such as working for a studio, or finding a company to sponsor my visa. But nothing ever added up.

In the end, it was – ridiculously – a paperwork issue that pushed me into following my dreams.

I spent the next year thinking: Why didn’t I do this sooner?

How do you choose where and what to shoot?

My basic approach to life and business was: “Just say yes.” I said yes to everything – the weird, the wonderful, the boring, the unexpected.

I did a lot of favors and gave away my time to friends who were doing exciting things.

Each project was like a seed that led to new projects, one or two new opportunities, and before long, my schedule was packed, shooting for brands like the Marriott Group or Starbucks, who I never imagined would be knocking on my door.

On the other hand, growing up in that small town in the Canadian Rockies taught me how important it is to support local; still to this day, I make small businesses my priority, whether that is a Taoye – a boutique hotel in Zhejiang – or Yaya’s Pasta in Jing’an.

Knowing my work has an impact on a small business means infinitely more to me than watching it get absorbed into the corporate machinery of a publicly listed company.

What is your favorite type of photograph to shoot?

There was a comment I started getting again and again when I posted photos from around China, a comment I started to crave: “I didn’t realize China was like this.”

The muted image I had of China before coming is a shared one, and I wanted to add color to people’s perception of the country I call home.

China is not one big homogenous landmass of chopsticks, factories and political headlines. It’s complicated, delicious, ambitious and creative, and I get to be up close and personal with all of that through my camera.

Over the years, stories about food have become a bigger part of the photos and documentaries I create.

I love watching dishes being delicately plated on the edge of a loud and chaotic kitchen, then chasing those ingredients back to their source – spending time with the people carefully producing them – then going back even further to understand how they came to be and the impact they have had on those communities.

The deeper I dug into these stories for companies like Zotter Chocolate, the more connected I felt. I recognized that maybe my choices of what chocolate bar I buy is much more meaningful than I expected to someone thousands of kilometers away.

Photography also becomes an incredible drive to explore.

As part of the Peddlers Gin team – the first China-based gin brand, started in Shanghai – when we set out to make a gin that represented the incredible diversity of flavors here in China; we sourced botanicals from all over the country – almonds near the border of Kyrgyzstan, Buddha’s Hand from Yunnan, our iconic Sichuan peppers.

Years later, I still have only scraped the surface of the stories that are within that bottle of gin.

Why are you so stoked about food?

My mother was a dietitian, and my father worked for the railway. Those two worlds collided when a 50kg bag of lentils fell off a train, and my father brought it home.

We spent what felt like the next 10 years eating lentils every day.

It was as much of a test of mother’s creativity in the kitchen as it was the malleability of lentils. Lentil pizza with a side of lentil stew is often what comes to mind when people ask if I miss my mother’s cooking. But, in reality, what she really was cooking up was a much deeper appreciation of food.

As a dietitian, food really meant something to my mother; food wasn’t mindless to her, it came with thought and an understanding of ‘why’ we eat.

Food should be thoughtful, not just what we are eating and whether it’s healthy, but also the stories behind it.

Our world revolves around food – imagine the journey your morning coffee went on to arrive in your cup. The stories along that path fascinate me.

We interact with food every day, so as a photographer these are images that people can connect to.

What is your advice to budding photographers?

I didn’t study photography; I’m not formally trained; I have virtually no art experience.

But that’s not what photography is about for me. If you want to be a photographer, be constantly asking yourself the question: “What is the story here?”

It doesn’t matter if you are shooting a dish at your favorite restaurant or the food waste processing plant that deals with what’s left over – let the story guide you.

What does that mean?

If I’m photographing a dinner party for Social Supply (a Shanghai-based creative experience marketing and design agency), it’s important to capture not just the plate of food, but to step back and capture the scene around it.

If I’m capturing a JFever concert, the audience is just as much part of the story as the rapper, so I make sure to obscure part of the stage with the silhouette of the crowd

If I’m taking photos of a mushroom harvest in Lishui, I make sure to find an angle that shows just how much they’ve harvested, but also a few close-ups of the weathered hands that are carefully sorting.

Like anything, photography requires practice. I’ve taken hundreds of thousands of photos this year alone. The more you shoot the better you will be.

So, start shooting – anything and everything, but especially your friends' businesses and projects.

Do I have a good camera? Yes, but some people still think that the photos I post from my phone were taken on that camera, so don’t confuse good gear with being a good photographer.

Some of my favorite photographers just use their phone, so start there, and start today.

Angles and lighting are everything – this is what brings emotion to your image. Let the light compliment the story you are trying to tell, and let the angle make that story pop.

Getting good at this takes time, but for me I like it when the light comes from the side; it means the subject pops from the background.

And I like to kneel down when I shoot, looking up slightly at my subject mostly to avoid having the ground or floor in the image.

Lastly, don’t let your camera get in the way of your life.

Being a photographer has sometimes been a barrier for me, a wall between me and whatever I’m capturing. I promise you that there are countless moments in life that are much more valuable as a memory rather than data on a hard drive.

Next, we take a deep dive into the favorite places Graeme has traveled in China, the inimitable experiences he’s had there, and the connection he’s felt with the people, places, subjects (and food) he’s captured through his camera lens.

Here is his story.

Which is your favorite place in China you have shot so far and why?

I’ve always had a rule of thumb, which is: if a friend invites you to their hometown, you go.

It doesn’t matter if that city is a seemingly dry or unimportant or an industrial city in Zhejiang or Henan or Gansu, get your shoes on.

I’ve never been disappointed by these trips: tucking into succulent, slow cooked lamb noodles in Deqing; trying to make sense of wedding rituals in the countryside outside of Xinyang; or waking up early for spicy breakfast noodle soup in Pingliang.

I'd never heard of these cities before, but now they hold a place in my heart.

China is a celebration of the unexpected; if you stick to your plans and follow a set path, you miss out on so much.

Getting lost here – in the language, the food, and the countryside – is what made me fall in love with China.

So whenever someone asks me for travel advice it is this: get lost; avoid the tourist destinations; go to your friend’s home town; get excited about food; be relentlessly curious about what’s happening around you; spend less time taking photos and more time really being there.

Here is something that fundamentally changed my view of China when I arrived. If you take a map of China and draw a straight line from the top right (on the border of Russia) to northern Myanmar, you cut the country in half, geographically.

A huge amount of what happens in China is to the east of this line: my little lane house; the incredible soup dumpling shop on Jianguo Lu and Gao’an Lu; bustling cities; tons of factories; Shanghai, Beijing, Shenzhen – 1.2 billion people live east of this line.

This is the Hu Line, named after geographer Hu Huanyong (胡焕庸).

About 5% of the population lives west of this line. It's mostly mountains, deserts, rolling grassland and high plateau. This is Xinjiang, Qinghai, Tibet, Inner Mongolia, Gansu – enormous, sprawling and fascinating provinces that few venture to.

These photos are taken in a Kazakh autonomous county in Gansu, along the border of Xinjian – a high plateau where I saw more Tibetan antelopes and camels than humans.

I think it's important to consider that this is what huge amounts of China looks like: vast dry lands rolling off into mountain ranges, with the squish of sand in your boots.

It's where China seems a little more like Canada than the smoggy sprawling cities and traffic jams I remember seeing on the news before I arrived.

I’ve recently adopted a new house rule: if I am opening a bottle of wine, it better be from China.

When I moved to Shanghai nearly a decade ago, you could get Great Wall wine in the convenience store, but it was a punchline.

China was producing good wines at the time, across several growing regions, and had been for years, but the best ones weren't cheap, and the cheap ones weren't very good.

There was a lot of drive to create a Bordeaux style of wine. Vines and wine makers were both often imported.

A few years ago, this began to change as wine makers like Ian Dai (from Xiaopu Winery in Ningxia) started to buy grapes from Chinese vineyards and made natural, easy going wines they could sell at a reasonable price.

Where there was once only a handful of wines like ‘The Last Warrior’ from Silver Heights that sat in the affordable and enjoyable range, there are now enough to fill my shelves at home: 聚 from Xiaopu; Sho Fang’s Tempranillo; Cabernet Sauvignon from Domaine Des Aromes; Muscat from Puchang...

The list goes on and on – and are now easily accessible through DrinKuaidi (via Eleme) and Simple Drinks (via Taobao).

Not all of these wines are from Ningxia, but if you are looking to nibble grapes off of vines, a wine tour out of Yinchuan is the place to start.

Bigger producers like Xige offer tours; boutique vineyards like Silver Heights do tastings; and quiet spots like Domaine Des Aromes might let you poke your head in if you're with the right guide, all padded out with lamb, spice, and noodles that play a big role in the incredible Hui cuisine of the region.

The incredible landscape that makes Guizhou so iconic also played a big role in keeping the region fairly isolated until recently.

That isolation meant that salts, vinegars and spices that were shaping Chinese cuisine weren’t as accessible in Guizhou, so fermentation became the most accessible flavoring in town.

Today, railways and highways now thread through the province’s spectacular limestone mountains, and although the sights are something to behold, you really remember the smells.

Sichuan next door is known for numbing spice (麻辣 mala) while Guizhou is known for sour spice (酸辣 suanla), which comes from a variety of fermentation methods, giving it that mouth-watering funk.

So when you are ready to level up from Guizhou restaurants in Shanghai like Shan Shi Liu or the inventive Oha Eatery, it might be time to fly to Guiyang.

It's a show of China's ingenuity, with some of the country's most interesting dishes from some of its most stunning farmlands.

Hainan became the tropical escape for most of us during the past few years: Sanya beach hotels; surfable breaks up the east coast; a population of the trendiest Chinese youth in Riyue Bay escaping the 9-9-6 grind.

I ended up filming a handful of short surf documentaries about this rising trend for Vans last year, but all of this is just along the coastline.

Hainan is an incredible story of Southeast Asian migration and movement. The island is further south than Hanoi, and it’s brimming with tropical fruit, seafood, and… cacao.

I’ve been lucky to film the story of chocolate from the trees in Africa, Latin America, Hawaii, and Southeast Asia all the way to the chocolate bars being made in Austria, so hearing there was cacao just up the road from where I was filming surfing was super exciting.

Cacao has been around for almost 70 years on Hainan, dating back to a group of Southeast Asian farmers who brought with them seeds and plants.

The cacao trees that were brought over were mostly shrugged off, but the quality was good enough for chocolate makers like Kessho and Jokelate from Shanghai, who have made fully Chinese bean-to-bar chocolate.

It’s yet another reminder of how diverse China is...

Want to hang out in -40 degree weather on a chair made of ice? Harbin.

Want to drink fresh coconuts on a beach? Wanning.

Want to ride a camel in a desert? Dunhuang.

Want to do it all in one weekend while eating a local chocolate bar? China.

It was the first time a restaurant owner I was dining with looked me dead in the eyes, smiled, and said, “You are going to have horrible diarrhea tomorrow.”

Chongqing hotpot traditionally uses a little bit of today's soup, boiled to sterilize, in the next day's preparation.

It's not unlike the idea of "master stocks" in Cantonese kitchens (where some sauces go back decades).

It's not cost-saving; rather it's flavor-building. And, after generations of this, the sauces pack some serious flavor.

Years ago, this practice was regulated out of existence (mostly) amid food safety scandals and an increase in domestic tourism.

I was in the city filming a hotpot base factory, and I got curious about how that change has affected the flavor of Chongqing’s most famous meal.

Later that day, halfway through a dinner with a restaurant owner, we started talking about it. He sized me up, leaned back in his chair, and shouted back to the kitchen. Most chefs keep a bit of that master stock hidden away, some small restaurants still serve them... and I made the cut.

As soon as the thick, crimson red oil was poured into our hotpot bowl, everything changed. The flavor was something else. Thousands of hotpot sessions, compiled and dripping off my piece of cow tripe.

I was sweating in seconds. Decades of chilies leaving their capsaicin in this oil.

I was buzzing.

Not all delicious food is comfortable, and Chongqing hotpot is a legendary example of that, especially with a local friend who knows the spots. As far as Chinese dining experiences go, Chongqing hotpot is one not to miss.

There just are two important tips: drink a lot of soy milk during dinner; and don’t book a morning flight home the next day.

When I think of caviar, I think of Russia. But the reality is that much of the world’s caviar comes from China. And some of the best comes from Sichuan's Hanyuan County (also famous for Sichuan peppercorns).

I remember when I was a child how "Made in China" meant cheap. But standing waist deep in a sturgeon tank filled with fresh mountain water, wrestling out a fish that will be harvested for high-end caviar, that phrase started to mean something else.

China, for so long, was a destination for traders. The Silk Road and the sea routes were carved around the globe just for a young Europe to get access to the finest silks and porcelain.

China has a stunning history of craftsmanship and care, whether that’s from the carefully curated Sichuan peppers farmed specifically for the emperors of the past; the caviar of today; or the future wines of Sichuan that are just being planted.

If you think Italy is the land of pasta, let me take you to the coal mining, wheat growing, industrial northern province of Shanxi.

Shanxi might not be the first on many people’s list of places to go; it’s easily confused with the somewhat more touristy Shaanxi province next door – lauded for Xi'an’s Terracotta Warriors.

But if you want to eat dozens of different types of noodles in a weekend, you are in the right place in Shanxi.

I’m working with Chris St. Cavish (a Shanghai-based chef, writer, and foodie) on a noodle book, and part of the legwork required is eating as many types of noodles as possible. Where else would you go?

Cat ear noodles, scissor cut noodles, knife cut noodles, pulled noodles, flicked noodles, dog tongue noodles, one long noodle for birthdays, noodles pressed by some lady on an enormous garlic press thing, ‘foreskin’ noodles (yup!), rolled noodles, shredded noodles, noodles, noodles, noodles.

Xinzhou even has a little ‘noodle town,’ and Daton – known for its knife cut noodles – is also home to some beautiful ancient compounds and grottos.

China has a wildly long history of fascinating food, and noodles, which vary from town to town. Thank goodness someone is writing a book about it.

When I started working at naked in Moganshan, the boutique hotel industry was booming.

Venturing out to Moganshan for a weekend escape from Shanghai was fairly common, and I was lucky to spend loads of time at their resorts filming, watching naked Castle getting built and eventually opened.

And, in the years after I left naked, Zhejiang remained a special place in my heart.

I started documenting the design and construction of a resort in Lishui called Taoye, situated in a small village called Songzhuang.

Many of these villages are barely half full; urbanization and opportunities in the city have left these towns with only their elderly population, who spend their days farming, cooking and finding warm spots in the sun to gossip.

Watching Taoye come to life in its little village was like seeing fresh air breathed into it – even the construction process fascinated me.

Old Chinese construction is often designed like a big puzzle; few nails are used as everything is carved to slot together perfectly, which means if you want to take it apart, it’s more like taking apart IKEA furniture than demolishing a house. Once you do your alterations, you just slot it back together again.

The narrow lanes of this 700 year old town meant that the work was mostly done by donkeys and by hand, right down to the few nails that are used – they were hand carved out of bamboo on site.

Zhejiang is ever changing, with new boutique hotels opening all the time.

Some exciting ones to watch for this year in Moganshan include MOOKE, which includes MOOKE&Co (a sort of ‘remote work haven’).

A new, younger generation is finding their way to Moganshan, putting coffee shops next to tea rooms and creating space for the young business owners, artists and chefs to keep this mountain escape fresh.

Borders may be open again, making breaks out of the country accessible, but there is so much to explore here in China – from down the road in Moganshan to the far and fascinating corners of this country, with delicious and sometimes unexpected meals around every corner.

When Graeme isn't working on visual stories about agriculture and life in the countryside, in Shanghai he shoots for a huge range of brands – from hotels to restaurants – and a variety of other products and businesses.

Check out his website at www.GraemeDYK.com or by scanning the QR code below:

Follow Graeme Kennedy on Instagram @graemedyk

[All images courtesy of Graeme Kennedy]

My name is Sophie Steiner, and welcome to my food-focused travel blog. This is a place to discover where and what to eat, drink, and do in Shanghai, Asia, and beyond. As an American based in Shanghai since 2015 as a food, beverage, travel, and lifestyle writer, I bring you the latest news on all things food and travel.

Your email address will not be published.

Be the first to comment!